Greenland Crossing Success

Expedition Trip Report: 2015 Greenland Crossing

Introduction

After leaving Greenland in April of 2014 following a failed crossing attempt I vowed never to return. My fingers were painfully frostbitten and the memory of the worst storm I had ever experienced was fresh. I was embarrassed about discovering that I was not strong enough to pull a 170 pound (77 kilogram) sledge for weeks on end and vividly recalled the hopeless exhaustion I felt at the end of each day on the ice. I was done with Greenland.

However, the odd thing about pain and discomfort is that after it has been removed you tend to forget all about it. In one of the great natural conspiracies that encourages people to do completely unreasonable things in the face of good evidence they can’t the phenomenon of selective memory kicks in and makes the untenable seem plausible once again.

…the odd thing about pain and discomfort is that after it has been removed you tend to forget all about it.

This is a long way of saying that six months after deciding never to return to Greenland I signed up for another attempt at the crossing. In May of 2015 I was back on the ice.

Improving the Odds

Based on my 2014 experience I knew that three problems had to be addressed for me to complete the crossing:

- Too much weight in the sledge.

- Inadequate hand protection.

- Awful weather.

Solving the weight problem was surprisingly easy. I learned that Børge Ousland offered a trip that used sled dogs to carry the bulk of the gear, giving the participants the freedom to ski most of the distance unburdened by sledges. This kind of trip seemed tailor-made for me and was the biggest factor by far in encouraging me to give the crossing another go.

My fragile fingers took a terrible beating in 2014 because I relied on a glove system that failed to meet expectations. The results were disastrous. For 2015 I substituted a new system that I field tested in very cold conditions before leaving for Greenland. I was sure that the new system would be up to the task.

…by choosing a west to east crossing instead of an east to west one I banked on gaining the considerable advantage of a later start.

The weather is always in the hands of the gods and no amount of planning can keep you from getting clobbered if you are unlucky. However, by choosing a west to east crossing instead of an east to west one I banked on gaining the considerable advantage of a later start. In 2014 I was on the ice on April 14; the 2015 crossing began on May 6. I felt that the three week difference would help keep temperatures at the start less bone-chillingly cold and hoped that by the time we arrived on the east coast the worst of the katabatic storms would be past.

Having addressed the problems as best as possible I took the plunge and signed on to Børge Ousland’s “Dogsledge Across Greenland” expedition. Like many things done from the comfort of one’s office at home, it was the work of a moment that gave no hint of the massive amount of effort that actually doing the crossing would be.

Getting There and Back

All west to east crossings require a trip to Kangerlussuaq, a small village of about five hundred permanent residents that is 200 miles (323 kilometers) north of Greenland’s capital, Nuuk. Oddly enough, the village supports the largest airport in the entire country. The airport was originally built by the United States during World War II to facilitate the ferrying of airplanes and materiel to Great Britain. During the Cold War it was repurposed to support the four Distant Early Warning Line bases that were built on Greenland in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The American presence is still evident today with LC-131 Hercules aircraft regularly going in and out to facilitate the National Science Foundation’s activities in the northern reaches of the icecap.

You have essentially two choices when travelling to Kangerlussuaq. When starting in Europe you can get a nonstop flight from Copenhagen. When starting from the United States the routing is more complicated. I found that my best option was to fly to Reykjavik, Iceland and then to Nuuk. I stayed overnight in Nuuk before going on to Kangerlussuaq.

When travelling home after completing the west to east crossing virtually everyone flies from Kulusuk, Greenland to Reykjavik City Airport. From there you take the bus to Keflavik, Reykjavik’s international airport, and then on to your final destination. Getting to Kulusuk is the most difficult link in the chain. For our group it required a helicopter flight from Isortoq (the expedition’s finishing point) to Tasiilaq, an overnight there and then another helicopter flight to Kulusuk.

If you do the bookings yourself, you need to know that Air Greenland is invisible to Expedia, Travelocity, Kayak and all the other usual travel websites. Unfortunately you cannot avoid using Air Greenland and navigating its byzantine website requires more patience than most people possess. Enlisting a travel agent to make the arrangements can save you a lot of frustration.

Expedition Staging

I arrived in Kangerlussuaq on May 4, two days before our scheduled departure for the ice. My hotel, the Polar Lodge, was conveniently located just a two minute walk from the airport terminal building.

…The new plan was for the dogsledge group and man-haulers to stay together for at least a week and not meet the dogs until we were 70 miles (113 kilometers) onto the icecap.

Our preparations in Kangerlussuaq consisted mainly of portioning out the food and confirming how the expedition would be run. In this last respect it immediately appeared that changes were in the offing. The original plan was for the dogsledge group (me and five others) to travel for three days in the company of another Børge Ousland group (five people who were man-hauling across Greenland). At that point, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) into the journey, we would meet up with the dogs and the two groups would split. The new plan was for the dogsledge group and man-haulers to stay together for at least a week and not meet the dogs until we were 70 miles (113 kilometers) onto the icecap.

The reason for the change had to do with the surprising logistics of our dogsledge expedition.

Instead of starting the crossing with us on the west coast, the dogs and their handlers started from Isortoq on the east coast in mid-April aiming to rendezvous with us on May 8. The rendezvous point was to be Dog Camp, a featureless GPS point 25 miles (40 kilometers) from the western edge of the ice. Because the best dogs are from the east coast and these sturdy fellows are unfazed by long journeys the expedition plan called for the dogs to travel fast and light 300-plus miles (484 kilometers) before we ever saw them. According to the plan, the dogs would arrive at Dog Camp on May 4, get four days of well-deserved rest and begin their eastward trek with us starting on May 9.

Unfortunately, the theoretically fast and light dash from Isortoq to Dog Camp turned into a much lengthier affair than anticipated. Bad weather and other woes slowed the dogs down and put them far behind schedule. As a result, the idea of us meeting the dogs 25 miles onto the ice was abandoned and Dog Camp was shifted to another GPS point 45 miles (73 kilometers) further east.

To make the going a bit easier for dogsledgers and man-haulers alike we divided our food and fuel into two buckets: an eight-day supply that would go with us and the balance that would be airlifted to Dog Camp via helicopter. This was a very sensible arrangement because from the start the organizers planned to supply Dog Camp by air. As per the plan, the dogs and handlers were expected to reach Dog Camp with very little left in the larder and were scheduled to get an air drop of roughly 2,000 pounds (909 kilograms) of supplies, the bulk of which was food for the dogs. We added most of our food and fuel to the helicopter’s load and by so doing each of us shaved about 25 pounds (11 kilograms) of weight from our sledges. This proved to be a very welcome subtraction and kept the weight of the sledges to about 100 pounds (45 kilograms) apiece.

Our food for the journey consisted of the usual collection of freeze-dried boil-in-the-bag dinners, massive amounts of chocolate, dried fruit, nuts, ramen noodle soup, cookies and oatmeal. A welcome addition was several days of “real food” that was prepared by the team in Kangerlussuaq. This was a hearty tomato and meat sauce that was served over pasta. In all, we dogsledgers were provisioned for twenty-one days on the ice and the man-haulers for twenty-six days.

The guide for the expedition was Bengt Rotmo, a 42 year old Norwegian with numerous Greenland crossings to his credit and a long list of achievements in the world’s coldest places. Among other things, Bengt has skied all the way to the South Pole, led an all-the-way North Pole expedition and skied the Northwest Passage (1,100 miles / 2,500 kilometers) in Canada. He was a veteran with impeccable credentials that immediately inspired confidence.

While Bengt was assigned to take the man-haulers all the way across Greenland, we knew that he would be with us only until Dog Camp. There we would meet Sigrid Ekran, another Norwegian, whose specialty was dog mushing and who would take our group of six the rest of the way. Sigrid was a 35 year old who earlier in the year had won the Finnmark race, Europe’s longest (620 miles / 1,000 kilometers) and most challenging dogsled race. She competed successfully in the Iditarod several times and won the Rookie of the Year award in 2007. While she had done the crossing once before as an assistant guide our expedition was the first that she would actually lead.

…It was immediately apparent that our dogsledge group was a well-prepared and experienced group of travelers.

It was immediately apparent that our dogsledge group was a well-prepared and experienced group of travelers. Unlike the man-haulers, who were all twenty-somethings, our group spanned an age range of 42 (Clare) to 67 (me). Among us we had two who had done the 7-Summits (Clare and Ian), a professional guide (Mike), a volunteer guide with the Norwegian Mountaineering Association (Chris) and three who had already skied to the North and South Poles (Clare, Ian and me). A quick summary of the team follows:

Clare: Irish medical doctor, 7-Summiter, all-the-way sledger to the South Pole and, with Mike, organizer of The Ice Project, a series of expeditions whose goal is to traverse the world’s greatest icecaps.

Mike: Irish adventurer, safety consultant, public speaker, mountain guide and Clare’s partner in The Ice Project. His and Clare’s blog about the Crossing can be read here (website) and here (pdf version).

Ian: British businessman, 7-Summiter, climber of Eiger Nordwand and ex-Army paratrooper. The Greenland crossing was the final leg of his “before age fifty” challenge of the 7-Summits, North Pole, South Pole and Greenland.

Chris: Oslo-based British executive and ex-Royal Navy nuclear submarine engineering officer. A hugely experienced telemark skier and guide with the Norwegian Mountaineering Association. His own excellent report on our journey is available here.

Anja: German speech therapist. She recently completed an expedition that traced Shackleton’s route across the mountains of South Georgia Island. Her recap of our Crossing adventure (German language with English translation) is available here.

Tom (me): US merchant banker from the great winter sports mecca of Houston, Texas. For me the Greenland crossing was the last leg of the Polar Trilogy of North Pole, South Pole and Greenland.

After a comfortable two days in Kangerlussuaq we boarded an old Mercedes Unimog and began the 20 mile (32 kilometer) drive to the ice. The trip took about ninety minutes and was bumpy but spectacular as we approached the alien landscape where land finally yielded to the ice. Great icefalls were in plain sight along the way and I was apprehensive about how we would surmount them. However, at the end of the trail we reached Point 660, a place where we could gain the icecap with relative ease. I was a little disappointed that Point 660 did not quite live up to its name. According to the consensus of our altimeters it was only about 500 meters (1,640 feet) above sea level. Where the other 160 meters went to was anyone’s guess.

Starting Out: Point 660 to Dog Camp (May 6-12)

It was simultaneously comforting and terrifying to go through the familiar rituals of donning skis, adjusting clothing and attaching sledge to harness. I dispatched the mechanical steps with practiced efficiency but had a very uncomfortable moment when the thought of actually having to ski across 350 miles (565 kilometers) of unforgiving ice sunk in. At home I could dismiss the 350 miles with a confident shrug. Standing at the edge of the icecap I found that shrugs did not come so easily. “One day at a time” became my mantra.

One thing that was a great boost to everyone’s morale was the weather. During our stay in Kangerlussuaq the temperature never got much below freezing and it was comfortable to be outside lightly dressed. When we arrived at Point 660 it was sunny and about 35°F (2°C). The continued good weather made preparing for the ice easy and, with Bengt in the lead, our caravan of twelve skiers set off at 4:30 in the afternoon. I vividly remembered the brutal cold that attacked me and my companions from the first second we arrived on the ice last year and was infinitely grateful that our start was in better conditions on this trip.

…the icefall section of the glacier was pure chaos to ski in.

While it was easy to get onto the ice and we thankfully did not have to traverse any barren patches, the icefall section of the glacier was pure chaos to ski in. The transitional area where the glacier thinned and tumbled into the land was dramatically humped and battle scared. The ice piled up in tremendous mounds and gouged deep corridors into the rocky earth. Our track through this area meandered randomly through slushy sections and hard blue ice. However, after a couple of hours we put the mountainous disturbances behind us and entered an area of house-sized bumps. It was here that we made our first camp. We stopped skiing at 7pm and, aided by the mild weather, had the tents up and stoves humming barely an hour later. In the tent I checked my GPS and saw that our two and a half hours of skiing had gained us a bit less than 2 miles (3 kilometers). Naturally, the tally would have been much higher if our actual track had been recorded.

Over the next few days the team settled into a rhythm and Bengt kept lengthening our time on skis. On our second day on the ice (May 7) we did five hour-long stages in an eight hour day. By our fifth day (May 10) we were doing eight hour-long stages in a ten hour day. Making and breaking camp added two hours off-skis work every day.

The grind was difficult but as the terrain became less disturbed our path straightened and we began to be rewarded with good daily mileage. Over the course of the second and third days the disturbances went from house-sized to truck-sized to basically flat. I sensed that we were finally on the inland ice and it was wonderful to gaze forward and see an uninterrupted sheet of ice stretching limitlessly to the horizon.

While the difficulties of the icefall were dropping away behind us, other challenges were lining up to take their place. The wind became our constant companion, pestering us and peppering us with sharp crystals of ice every moment of the day. Every time we stopped for a rest break the wind was there to chill us and we had to be careful to have down coats and windbreakers readily at hand. Paradoxically, the thing that made the chilling effect of the wind much worse was that the weather remained warm and you could not avoid sweating. Sweaty skin and a buffeting wind make a miserable combination.

The warm temperatures also took their toll on snow conditions. By the third day we were so beset by sticky snow that I began to have flashbacks to the struggle I had pulling my sledge last year. The problem was that giant heavy cakes of gluey ice would adhere to the bottoms of everyone’s skis. This robbed the skis of glide and made it feel as if we were skiing on flypaper. After a few hours of pure torture we removed skins from our skis to see whether that would help. Happily it did and we were glad to trade the occasional bit of backsliding for better overall forward progress.

Tent life also settled into a routine. I was with Bengt and Anja. Mike plus Clare and Ian plus Chris shared the other two tents. From the first night I could see that this trip had big advantages over my previous one. Last year we built a wall to protect the tents from the wind every single day. This added a huge amount of work to the sledging day and always came at the time when we were the most tired. Bengt dismissed the idea of wall-building as silly. He reasoned that the tents were purpose-built to survive windstorms and said that if we ever had to face the dreaded Greenlandic piteraq, his preferred strategy was to dig a platform for the tent a couple of feet into the ice and reduce its exposure in that way. I was grateful beyond words that we would not be building any walls on this trip.

In addition, it immediately appeared that we would be more comfortable inside the tent than I was last year. Rather than confining all cooking activities to a snow hole in the vestibule, Bengt brought the stove inside the tent where its heat could warm us and dry wet gear in addition to melting ice. I remembered the torture of putting on hard-frozen facemasks and gloves last year and was happy to forego that experience this time round.

…our progress slowed to a crawl for an hour as Bengt meticulously probed the route for hidden crevasses.

You could tell that Bengt was absolutely at home and in his element on the icecap. He used a compass to set our course and was adept at keeping our line of travel perfectly straight. That kind of navigational efficiency cannot be achieved without years of practice and it was encouraging to know that our hard-won miles were not being wasted. The experience factor also was demonstrated on Day #4 (May 9) when our progress slowed to a crawl for an hour as Bengt meticulously probed the route for hidden crevasses. I could not understand what triggered his caution because the ice in the probed area looked identical to that both before and after it. Bengt later explained that he had noted heavy crevassing in this location during a crossing he had done a few months before. To be safe he recorded a GPS waypoint for the area and probed it to safeguard our march. He agreed that there was no visible clue but noted that crevasses can be very stealthy. Better safe than sorry!

Our progress across the ice was anything but fast. Even in good conditions the sledging was always physically demanding and our best pre-Dog Camp effort (Day #6) netted us just 15 miles (24 kilometers). The explanation was straightforward: it was very hard to drag a 100-pound sledge uphill and into the wind. In our first six days on the trail we gained 3,750 feet (1,144 meters) in altitude. It seemed a pity that the ascent was so gradual that the only things that gave us any clue that we were going uphill were the daily altimeter readings and our moaning legs. This is not to suggest that we would have preferred a steeper ascent. It was just that the apparent flatness of the terrain had the disconcerting effect of making us think that we were all a bunch of weaklings. I was a little depressed that our best efforts for each long hour of work netted us less than 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) of forward progress. The thought that we had to cover 350 of those hard-won miles (565 kilometers) was sobering in the extreme.

By the end of five days on the trail I was thoroughly sick of pulling my sledge and the extraordinary sameness of the landscape had long since eclipsed my feeling of being engaged in a great adventure with one of sheer boredom. It was not lost on me how fickle people can be. While there are no official records of Greenland crossings an educated guess is that fewer than two thousand people have made the attempt since Fridtjof Nansen’s first crossing in 1888. An infinitesimally small fraction of the world’s population! It made me feel a bit unworthy to be bored in the midst of an enterprise so uniquely rare. However, a quick poll of my teammates revealed that they were bored as well. All of us looked forward with great anticipation to reaching Dog Camp. It was like the Promised Land: a place where we could ditch our burdensome sledges and enjoy the novel camaraderie of the dogs. I had the coordinates of Dog Camp marked in my GPS and was counting down the miles to go. Every time I had to heave my sledge over a bit of sastrugi the happy thought of Dog Camp glittered in my imagination.

…equipment problems! Visions of disaster danced in my head.

On May 11 (Day #6) my boredom was replaced with panic when my left ski, which had been feeling slightly wonky for a couple of days, abruptly fell off my boot. The bad part was that the binding had also parted company with the ski and was still hanging on to the boot. Upon examination it was apparent that the front-most of the three screws that held the binding to the ski had sheared at the head. This put strain on the other two attachment screws and made the body of the binding work like a lever against them with each forward step. Eventually the screws tore loose. Visions of disaster danced in my head. We were barely 55 miles (89 kilometers) into the crossing and my skis were in ruins. My stomach churned at the thought of having to abandon the crossing and being ignominiously dragged off the ice by helicopter. I have seldom felt quite so awful.

Proving the inestimable value of experience, Bengt said “okay” and dug into his toolkit. Aided and abetted by the always optimistic and mechanically adept Chris and Lisa, a genuinely helpful member of the man-hauler group who had a spare screw in her extras kit, Bengt fixed the broken bits within a half hour of stopping. Bengt’s work was truly impressive. He shifted the binding an inch forward of its original location, punched three new mounting holes and screwed the binding down securely in its new location…all with his mittens on!

I was grateful beyond words to be back on my skis. However, for days afterward I suffered gigantic anxiety every time my skis squeaked. They squeaked with every single step. I was frustrated about my equipment fiasco because I had purposely chosen the combination of Scarpa T4 boots, Nordic Norm (75 mm) Voile bindings and Madshus EON skis because I thought that they would be absolutely bulletproof. I thought that there was no binding on earth simpler than the three-pin Voile. Yet, it had failed.

I instantly became a fan of the New Nordic Norm (Backcountry) bindings that all the other members of the group (except for Lisa) were using. I eyed them enviously at every stop. Meanwhile I was stuck with the Voiles and every time I clicked down on the lever that cinched the duckbill of the boot into the binding I was stressed that the whole thing would come apart again. This horrible vision never left my consciousness until the trip was over and all skiing was done.

May 12 (Day #7) dawned bright and cold (8°F / minus 13°C) and was a big day for all of us because we knew that we would reach Dog Camp that afternoon. It was doubly cheering to know that our destination was just 10 miles (16 kilometers) away and that we would have a short sledging day. After three particularly long days on skis I was very grateful for a short one. Also, it was encouraging to know that at day’s end we would have a third of the scheduled twenty-one days of the trip behind us. For me the one week mark was a milestone worth celebrating.

…As we approached the dogs saw us and started howling excitedly.

It was surprising that on the utterly featureless icecap we were not able to see Dog Camp until we were just a mile away. It seemed like forever before the specks on the horizon resolved themselves into tents and other recognizable objects. As we approached the dogs saw us and started howling excitedly. There were thirty-two of them and they made an incredible racket. They were looking forward to seeing new faces as much as we were. Both Sigrid, our guide for the balance of the trip, and Salo, the native Greenlander in charge of the dogs, came out to greet us smiling from ear to ear. It was a wonderful welcome. The fact that Salo spoke not a word of English and us not a word of Greenlandic made no difference at all.

Naturally, the six of us who made up the dogsledge group were a lot more excited to see the dogs than our man-hauler companions. The man-haulers seemed as amused at us carrying on with the dogs as with the dogs themselves. With the practiced insouciance that all Millennials seem to have baked into their bones the man-haulers regarded the scene with indulgent patience and retired to their tents. To be fair, they could not afford to get emotionally attached to the dogs. We all reasonably thought that once the two groups parted company in the morning we would never see each other again for the balance of the trip.

After dinner Sigrid gathered us together and outlined how the expedition would be run. In a nutshell, the plan was for Salo to take charge of the huge 14 foot (4.3 meter) sledge and its team of sixteen dogs, Sigrid would take charge of a 12 foot (3.7 meter) sledge and its team of eight dogs and we (!!!) would get the other 12 foot sledge and eight dogs. On a daily rotating basis, one of us would be assigned to assist Sigrid, two would run our sledge and three would act as lead skiers. Salo would handle the big sledge by himself. She explained that the lead skiers would be the navigators for the group. By staying out in front of the caravan the lead skiers would set the route and be the target that Salo’s dogs would chase. As the most experienced Greenlandic-style musher Salo’s sledge would be first in line, Sigrid’s second and ours third. It came as a profound surprise to me that a sledge and one of the dog teams would be given to us to run. The expedition brochure never hinted that this was part of the program and we were all surprised. How did three sledges and dog teams make it to Dog Camp with just two drivers? They didn’t. A third driver accompanied Sigrid and Salo. Sigrid’s good friend Kristin was helicoptered off the ice when the supplies were flown in three days before we reached Dog Camp.

Dog Camp to DYE-2 (May 13-15)

We celebrated our arrival at Dog Camp by sleeping in until 9am the next day. It was well that we did because it was minus 3°F (minus 19°C) overnight and we were all happy for some extra time in our warm sleeping bags. Our sleep was blissful as usual (sledging really knocks you out) and the incessant “singing” of the dogs was no impediment at all. I was actually comforted by that ever-present reminder that our canine companions were at hand.

The day started on a high note when Bengt came around to collect the dogsledgers’ sledges. We no longer needed them and to keep the center of gravity of man-haulers’ sledges as low as possible the plan was for them to each pull two sledges. This was a smart arrangement that had the added benefit of reducing the profile the sledges presented to the wind. In any event, I was absolutely delighted to see my sledge go away forever. I eagerly looked forward to enjoying the freedom of skiing without that heavy impediment and, for the first time of the trip, permitted myself to think about our next major waypoint of the crossing, the long-abandoned DYE-2 radar station. According to my GPS it was just 45 miles (72 kilometers) away.

…It was an incredible luxury to ski unburdened…I felt like nothing in life could be better than free-skiing on the Greenland icecap!

Before we could go anywhere we had to learn the new routines of packing the dogsleds, fastening tarpaulins and tying everything down. Chris and Ian proved to be brilliant at this work. The packing took two solid hours and I nearly froze to death in the process. Luckily, I had volunteered to be one of the lead skiers for the day and Mike, Anja and I were able to start out while the others were finishing preparation of the sledges. I had a moment of pure joy when setting off. It was an incredible luxury to ski unburdened and I quickly warmed up. I felt like nothing in life could be better than free-skiing on the Greenland icecap!

After an hour and a half we caught and quickly passed Bengt and the man-haulers. They had started out forty-five minutes before us and were just getting accustomed to their newly increased loads. Naturally, the speed contest between us free-skiers and them with their 130 pound (59 kilogram) loads was no contest at all. I thanked my lucky stars that I had chosen to do the trip with the dogs.

It came as something of a shock to us lead skiers that we were steadily outdistancing the dogs. On several occasions we had to stop for lengthy breaks to allow the dogs to stay in contact with us. This was quite the opposite of what we expected. As we looked back we eventually realized that all was not going well in dog-land. From what we could see, it looked like Ian and Chris were having an awful time keeping their dogsledge moving and Sigrid and Clare were moving in the fashion of a sine wave with their team. Salo was continually stopping his team to allow the others to catch up. During the course of six and a half hours on the trail we only came together once. Mike and I debated what was going on but never could make any sense of the spectacle. One guess was that the buffeting ice-laden headwind that had plagued us all day was keeping the dogs from seeing properly. We were happy when Salo and Sigrid called an early halt to the day after just 12 miles (19 kilometers) of traveling.

I got a recap of the day’s misadventures from Ian once we had built camp and were in the tents. He said that he and Chris were thrown into the deep end of the dog-pool and basically had to learn how to manage the team all on their own. They were taught the Greenlandic words “Goh!” (go) and “Arronyah!” (lie down), given an impressive looking but thoroughly useless whip (sort of like the whip equivalent to a child’s pop-gun) and told to follow the train as best they could. Not surprisingly chaos quickly ensued and the dogs, whose work ethic disappeared the moment they realized they were in non-expert hands, cooperated minimally with the effort to get a move on. Ian and Chris had an exhausting time pushing the sledge, exhorting the dogs to pull and untangling the mess that was created every time one of them decided to have a fight with another. Ian said that sledge pulling was nothing compared to the work of running the dog team.

We had a group dinner that night in Sigrid’s tent and all eight of us squeezed in. During dinner Sigrid gave us some more information about the dogs. It turned out that two of the teams (Salo’s and ours) were owned by Salo. She said that these were all topnotch, experienced dogs. The other team, recruited with some misgivings from Salo’s neighbor, was made up of inexperienced rookies. She said that it was simply a fact of life in Greenland that resources are scarce and you cannot always get what you want. She said that “the shit team” had been a source of frustration on the journey from Isortoq to Dog Camp and that they were even worse now that they were being asked to pull a heavier load. Despite her best efforts and Clare’s determined assistance the shit team wandered all over the landscape. With her hands more than full with the rotten dogs, Sigrid was not able to help Chris and Ian get better work out of their (theoretically) good ones. We hoped for better times tomorrow. Mike and I were scheduled to mush the “good team” the next day.

Once we had separated from the man-haulers we decided to rotate tent assignments every couple of days so that we dogsledgers (including Sigrid and Salo) could all get to know each other better. The only exception to the rule was Mike and Clare who were a couple in real life and stayed together for the duration of the trip. The reality of the situation was that sledging, whether dog-assisted or not, was a solitary business. When lead skiing the work was very intense since everyone wanted to contribute as many miles as possible to the team’s progress. Opportunities for conversation were limited and even during the hourly breaks the need to hydrate and eat took precedence over socializing. It was much the same when assigned to the dogsleds. Most of the time the work precluded talk. As a consequence, the only real time we had for conversation was in the tents at day’s end and our occasional group dinners.

It was fun to share a tent with Ian on the journey to DYE-2 because he is a great fellow and has one of the most impressive adventuring resumes of anyone I have ever met. I doubt whether there is anyone else on earth who can count the 7-Summits, North Pole, South Pole, Greenland Crossing and the ferociously perilous north face of the Eiger among their accomplishments. Like most successful people Ian was goal oriented: having already done the 7-Summits and Last Degree expeditions to the North and South Poles, he set his sights on Greenland and determined to complete his personal grand slam of adventuring before he reached age fifty. He was just a few weeks short of that milestone when he began the trip.

On Day #9 (May 14) we got another leisurely start and did not emerge from the tents until 9am. It took a bit more than an hour and a half to get the sledges and dogs organized for travel. The free skiers for the day, Chris, Ian and Clare, started out ahead of us and set a strong pace.

…Learning from yesterday’s fiasco, Salo attached a rope from his sledge to Sigrid’s and this kept the rotten team more-or-less on the straight and narrow.

Mike and I ran the “good” dog-team and it did not go too badly. Mike proved to be an adaptable and patient dog handler and we both had the benefit of occasional coaching from Sigrid. Learning from yesterday’s fiasco, Salo attached a rope from his sledge to Sigrid’s and this kept the rotten team more-or-less on the straight and narrow. Of course, it also gave the laziest of them carte blanche to cease pulling at all and let Salo’s dogs do all the work. Sigrid had to spend a lot of time threatening and cajoling her team to work. But, in the odd moments when her dogs were cooperating she was able to come back to Mike and me and help keep us from falling too far behind. I concluded that the dogs were really very smart: the second they saw Sigrid coming in their direction they instantly mended their evil ways. It was perfectly clear that having a third professional dog musher on the crossing team would have made the going a lot better for all of us.

To my great satisfaction I was liberated from my dog-mushing duties halfway through the day. I switched places with Ian and joined Chris and Clare on the lead-skiing party. The skiing was rigorous because we worked hard to set a fast pace. Nonetheless, I was much happier to be skiing than driving the dogs. Despite the usual strong head wind, skiing conditions were excellent. By pushing ourselves we made the most of the favorable conditions and finished the day with 19 miles (31 kilometers) of forward progress. This was wonderfully encouraging, all the more so because the vertical ascent was also quite substantial at 609 feet (186 meters).

The day ended on a high note when, not far from our stopping point, we saw DYE-2 glimmering in the distance. It was just a tiny gray dot on the limitless expanse of the icecap but was definitely there! When inside the tent I checked my GPS I saw that it was just 13 miles (21 kilometers) away. This was great news because it meant that the next day would be a short sledging day and we would have plenty of time to explore this remarkable relic of the Cold War.

It was a very cold minus 8°F (minus 23°C) overnight and as usual most of us brought a Nalgene filled with near-boiling water into our sleeping bags. After a full day’s exposure to the relentless cold of the inland ice, clutching the hot water bottle at night was an incredible luxury. Our camp (Camp 9) was at a latitude just above the Arctic Circle. With the sun always above the horizon it was bright enough to read while in the tent and night and day were barely distinguishable.

The trip to DYE-2 on May 15 went by in a flash despite continued problems with the dogs. Once again, conditions on the ice were outstanding and the going good for both dogs and humans. The only snags were that 1) the dogs pulling our sled (this time with Clare and me in command) resumed their errant ways, 2) the rotten dogs on Sigrid’s sled figured out that they did not have to pull at all because they could rely on a tow from Salo’s sled and 3) Salo’s dogs rapidly got exhausted pulling two sleds instead of one. The only thing that saved the day was that the ice was so firm and conducive to travel that it was impossible not to make progress. After only five hours in harness we arrived at DYE-2 and made camp right at its doorstep. I was elated to be there. We did not know it at the time but it turned out that our average speed for the day was the best we would have for the entire trip.

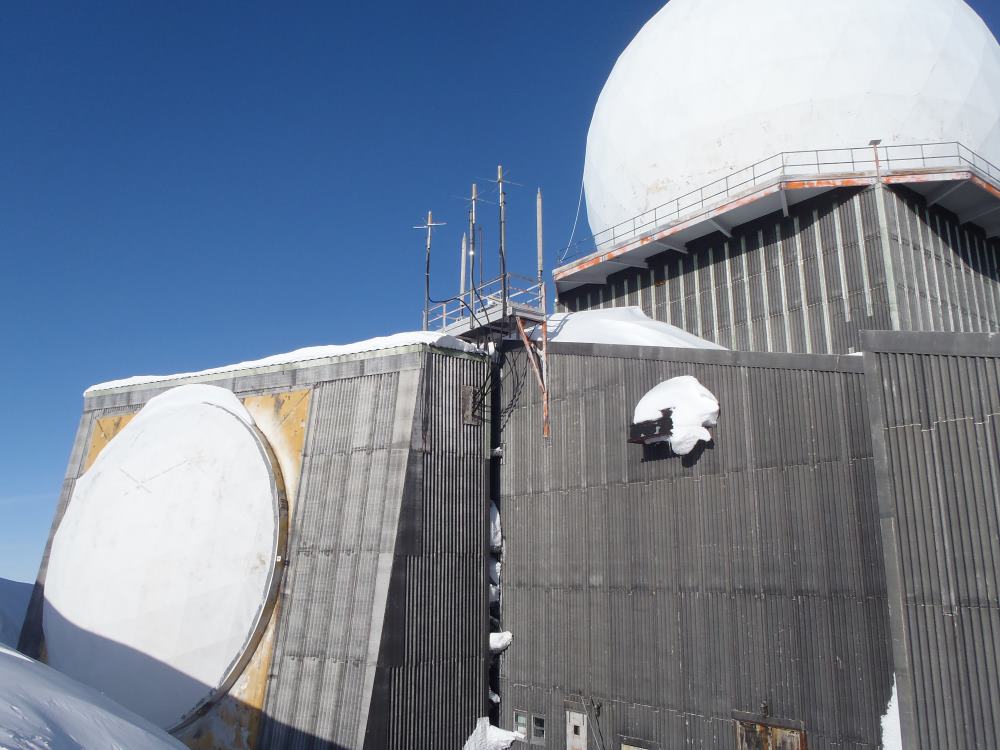

DYE-2[1] had loomed large in my thoughts for months before going to Greenland. It had much the same appeal to me as time-capsules do to the public. It was a gigantic structure, roughly 120 feet (37 meters) square enclosing 43,000 square feet (4,000 square meters) of floor space. It was topped with an 60 foot (18 meter) diameter radome that housed its raison d’être, a long range radar antenna that once scanned the heavens twenty-four hours per day. Projecting from the main structure like colossal ears were six side-facing tropospheric scatter communications antennas that emphasized its otherworldly appearance. It was built by the US Air Force in 1959 as part of the Distant Early Warning Line, a string of fifty-eight radar bases that stretched from Alaska to Iceland. The mission of each DEW Line station was to detect Soviet aircraft bent on bombing American cities and give a few hours advance warning of the impending nuclear attack. Countless billions of dollars were spent constructing the DEW Line and seeing DYE-2 in person it was instantly clear why the enterprise was so very expensive. Though weathered by fifty-six Greenlandic winters and standing abandoned since 1988 DYE-2 still had an aura of invincibility about it. To anyone who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s (me!) it was a vivid reminder of those dangerous days when the threat of nuclear annihilation weighed on everyone’s mind. It occurred to me that my children probably could not describe what the term “nuclear winter” meant. As an eleven year old in 1959 I could and all of my contemporaries could as well. It was good that history evolved in a way that allowed such terms to disappear from the lexicon and for structures such as DYE-2 to become mere curiosities.

[1] For the record, the official US Air Force name for the station was “DYE-2” rather than “Dye II” or the other variants commonly seen. Surprisingly, in the acronym-cluttered world of the military, the “DYE” in DYE-2 was not an acronym at all. It referred to Cape Dyer on Baffin Island, Canada where the regional coordinating base for the Greenland DEW Line stations was located. This base was called “DYE-Main” and the four Greenland stations “DYE-1” through “DYE-4”. DYE-3 is still largely intact and sits on the icecap in a location even more remote than DYE-2’s. The other DYEs (in Kangerlussuaq and Kulusuk) have been dismantled and removed.

We had a group dinner outside the tents before embarking on our exploration of the interior of DYE-2. The food was great (for the first time we broke into our store of “real food”—pasta in meat sauce) and everyone was in high spirits about reaching this landmark. However, the experiment of eating outdoors was judged a failure. Although the evening was sunny and we all bundled up in layers of fleece and down, it was just too cold to be outside doing something as sedentary as eating. We hastened to finish and get on with the exploration.

…We crawled into the structure through a broken door.

As a veteran of several visits to DYE-2, Salo led us inside. The way in was not straightforward. It involved shoveling steps down the huge snowdrift in the lee of the building and then climbing an exterior metal stairway to a broken door. We crawled into the structure through the door.

With headlamps lighting the dark corridors we spent a couple of hours touring the facility. The station was abandoned with just two days advance warning in September of 1988. Evidence of the hasty retreat was everywhere. No effort was made to salvage anything and there were storerooms filled with precisely organized racks of spare parts. Virtually everything of a mechanical nature that was needed to keep the place operational was included in the spare parts inventory. In the kitchen and adjacent pantry cases upon cases of now-frozen beer and soft drinks stood at the ready. Sacks of flour, sugar, condiments and spices were piled high. A plastic-wrapped ham stood on a stainless steel counter awaiting a cook’s attentions. Locked in eternal frost much of the food still looked perfectly edible in sealed containers that echoed the style of the late 1980s.

Despite the inevitable vandalism that it had endured during twenty-seven years of abandonment, it was easy to imagine what life in DYE-2 was like in its heyday. The accommodation quarters for staffers were Spartan but comfortable looking. Books and magazines stood on night tables and the beds still had their foam mattresses. A few of the rooms had windows and were flooded with light. In the common areas of the station there were recreational facilities (bar, pool table, shuffleboard table, movie room, exercise equipment) that looked positively inviting. The normal complement of personnel included fourteen people but there was room for up to thirty-five. All were civilian contractors who worked nine hour shifts six days per week. Even though it had a national defense mission, no military personnel were ever permanently assigned to DYE-2. It reminded me powerfully of South Pole Station in Antarctica. It was like a spaceship, providing warmth and sustenance in a place where all the forces of nature were aligned to keep men away.

…the huge radar antenna revolved silently around its pedestal when pushed!

One of the highlights of the tour was going up into the radome. The huge Bendix radar antenna dominated the space. To my amazement it revolved silently around its pedestal when pushed. This led me to wonder about why the station had been so hastily abandoned. The official reason was that “differential settlement” had created stresses that put the building in imminent danger of collapse. The easy movement of the radar antenna was cogent testimony to the fact that whatever tilting the engineers were alarmed about in 1988 had not progressed at all in the intervening decades. It is possible that the military was simply looking for a plausible reason to exit the DYE bases. By 1988 the threat of attack by the kind of “airbreathing” aircraft that the DEW Line was designed to detect had long-since been replaced by that of intercontinental ballistic missiles. More fundamentally, spy satellites made the job of the DEW Line bases redundant. Obsolete or not, it still seemed a bit sad to me that DYE-2 was abandoned so wastefully and unceremoniously.

When we returned from the visit, Sigrid had a special treat for us. Heaven knows how she managed it but she had baked a platter of brownies for us to share. What a wonderful way to end an eventful day!

DYE-2 to Summit

We got a very late start on Day #11 due to foggy conditions that persisted until 1pm. The fog would not have posed a problem if we were man-hauling but effectively stopped our dogsledge operations. The reason was that the dogs depended on a target to chase after and became confused when the target was shrouded in mist.

When we finally did get underway, the going was excellent. Chris, Clare and I were the lead skiers for the day and we made the most of the good conditions. In six and a half hours we covered more than 17 miles (28 kilometers) and ascended 453 feet (138 meters). We wanted to keep going but could not for fear of interrupting the dogs’ feeding schedule.

The altitude gain was significant because it brought us to within 900 vertical feet (274 meters) of Summit, the highest point we would pass on the crossing. We all eagerly looked forward to reaching Summit because from that point on it was literally downhill all the way to the east coast. Like most waypoints on the inland ice, Summit was an unmarked and unremarkable GPS point. Nonetheless, it was gigantically important to us because we assumed that all of our travelling difficulties would disappear and the dogs would immediately become paragons of canine virtue once we began the descent. We reckoned that Summit was less than 50 miles (80 kilometers) away and that we would make the distance in two days.

I was sharing a tent with Sigrid and enjoyed her company. She was a true outdoorsperson. She loved expeditioning and was happy to live in a tent for weeks on end. She said that after finishing the crossing she was almost immediately going to Svalbard for a month-long expedition there. Despite the unaccustomed pressures of her first lead guiding assignment she was cheerful, optimistic and pleasant at all times.

I was happy with the way Day #11 went and was encouraged to reflect that our trip across the ice was halfway finished, in days if not in miles. DYE-2 had dropped below the horizon and it was amazing to think that we would not see another man-made object until we reached Isortoq. Also, it transpired that the timing of our trip had an unexpected benefit. A little over a mile (2 kilometers) to the east of DYE-2 there was a landing strip (Camp Raven) where US Air Force trains pilots how to land ski-equipped LC-131 cargo planes on the ice. We luckily passed by just as one of these turboprop giants was landing.

Stormbound

Greenland giveth, Greenland taketh away.

May 17 and 18 were…relaxing. Sigrid was warned via satellite phone that a massive storm was headed our way and the prediction proved to be 100% accurate. For two entire days we were pinned down and unable to move. It was furiously awful outside and the only time I ventured out was to answer nature’s call. How does one attend to bodily functions on the icecap? As fast as one can manage! The upside of these ventures into the maelstrom was that you would return to the tent with the profound inner peace that only a calm stomach and empty pee bottle can bring.

We diverted ourselves with two group dinners during the storm. May 17 was Constitution Day in Norway and Chris and Sigrid enthusiastically threw themselves into preparations. They decorated the tent with Norwegian and Greenland flags and happily described memories of Constitution Days past. Although not a native Norwegian, Chris lives there, is fluent in the language and is married to a Norwegian. He clearly missed being away from his family on this important holiday. Sigrid shared some photos and videos of family and friends from last year’s celebration.

…For some reason our allotment of freeze dry packets contained a disproportionate number of the “curried cod” flavor. It was universally loathed.

At the group dinner on May 18, we had more of the delicious “real food” and it was a welcome break from the freeze dried stuff. For some reason our allotment of freeze dry packets contained a disproportionate number of the “curried cod” flavor. It was universally loathed. That it was eaten at all was a testament to the power of the ice over the appetite.

Mike and Clare went the extra mile for everyone’s benefit by laboriously preparing a thermos of fresh-brewed coffee and bringing Baileys Irish Cream to put in it. They were unanimously nominated for sainthood.

On Again

Day #14 (May 19) dawned cold (minus 10°F / minus 23°C) but encouragingly. The weather report predicted a turn for the worse in the afternoon so we got up at 5am to make an early start. The sleds and tents were engulfed in snow. You could not so much see a sled but a snowy lump where you thought the sled might be. It took a lot of time to get underway. Trying something different, it was decided to do a switchover of lead skiing duties at midday. Ian, Anja and Mike had the morning shift and Chris, Clare and I were scheduled to take over in the afternoon.

By the time we finally got underway at 9:30am conditions had deteriorated terribly. The wind was bitingly cold and loose unconsolidated snow made the dogs’ job miserable. However, the biggest problem was the lack of visibility. The lead skiers could only go a couple of hundred yards before being lost to sight. Progress all through the morning was in fits and starts. We would stop the dogs, let the skiers almost fade from view and then promptly catch up. My hands got extremely cold during the periods the dogs were stopped and I longed for the switchover so I could get them into my super-warm pogies. The pogies were like mittens on steroids. They attached directly to the ski poles and made my hands impervious to the worst cold Greenland could throw at them.

Conditions moderated in the afternoon and everyone’s epic work allowed us to finish the day with a goal-equaling 30 kilometers (18.7 miles) of progress. Given the fact that conditions in the morning were so bad that I feared the day would be scrubbed before it began, the team’s record for the day was thoroughly impressive.

Off Again

We woke on the morning of May 20 (Day #15) with high hopes for another 30 kilometer day. I had tented the night before with Salo and quickly came to appreciate the benefits of his company. He was incredibly adept at making camp and producing brews in evening and morning. Best of all, he appreciated in-tent warmth and kept a small primus stove going anytime we were awake. It was sheer luxury to retire to a warm tent after a long day on the ice. While the language barrier prevented conversation, Salo radiated good cheer and friendliness. To all of us he was also the undisputed heavyweight champion of dog mushing. Salo could make an errant dog mend its evil ways with a glance. It was interesting to observe him and his team during rest breaks. The dogs often gathered around him looking for love. A pat or a word made them content. This was very impressive because the dogs were anything but cute and cuddly. They were single-purpose working animals just a couple of DNA strands away from wolves. Because of a powerful alpha-dog instinct they were profoundly unsuitable as house pets. They constantly fought among themselves and when chained up at night had to be picketed in a way that prevented them from reaching each other. I learned from Sigrid that the “Greenland Dog” breed (canis lupus familiaris) was jealously guarded and that strict regulations were on the books to keep the bloodlines pure. In the right hands they were hardworking and tireless. They seemed absolutely invulnerable to the cold.

…Unfortunately, things went from bad to worse.

Despite a promising start, the weather quickly deteriorated and our progress was reduced to a crawl. Sigrid thought that by lead-skiing alone she could set a quicker pace for the dogs so she called Mike, Ian and Anja back. As an experiment she had Ian and Anja tie into the rope between Salo’s team and the rotten dogs to see whether they could get a tow as well. Unfortunately, things went from bad to worse. Skiing alone, Sigrid found navigation into the face of the buffeting wind next to impossible. Her track wandered all over creation. Back on the sledges, we found the dogs reluctant to move and their progress jerky in the extreme. The towing experiment went completely awry and Ian suffered a hard fall. Weeks later he had to have surgery to repair the damage. It was a testament to his toughness that he continued for the rest of the expedition without complaint.

After a hellish three hours on the trail and less than 5 miles (8 kilometers) of progress we called it quits. Building tents in the howling gale was unspeakable business. I have never seen tents erected in such terrible conditions. Chris and Ian distinguished themselves as take-charge masters while Salo and Sigrid were picketing the dogs. I would have never been able to erect the tent without their help. For my efforts I suffered four frost-nipped fingers.

It was remarkable how quickly life improved from terrifyingly awful to perfectly comfortable after entering the tent and getting the stove going. I almost immediately forgot about the day’s troubles and luxuriated in the warmth of Salo’s stove. I was annoyed that frostbite blisters had formed on my fingers but knew from experience that the damage was superficial. To prevent the problem from getting worse I cobbled together an additional layer of insulation for my mittens. This proved to be reasonably effective but I deeply regretted that I could not use my pogies when assigned to the dog teams.

In the late afternoon Sigrid went tent-hopping to give us the weather report and plan. In summary, the weather report was not promising. The Danish Meteorological Service predicted stormy conditions through 3am, better conditions from then until 2pm and a resumption of the storm thereafter. We had been receiving these highly detailed reports from the beginning of the expedition and they were surprisingly accurate. As a consequence we decided to get up at 3am the next morning and try to take advantage of the weather window. We were very conscious that with today ending in shambles and two previous days lost to storms our hopes of finishing the trip on schedule were gone. Our only alternative was to press forward as best we could whenever the weather allowed.

It was miserable waking up early and digging out in the cold aftermath of the storm. Once again, everything was thoroughly buried in the snow. But, it was tremendously cheering to see blue skies and a crisp sharp horizon. It was a reasonable 3°F (minus 16°C) when we started out.

The first couple of hours on the trail were a disaster. We resumed the experiment of having the dogs pull everyone but soon had to abandon that. Sigrid took off as the sole lead skier and that was also a big mess. Without her nearby the dogs on the second and third teams would not behave at all and progress was minimal. The next thing we tried was to have two lead skiers on two hour rotations. Bingo! That was to the key to success.

For much of the day I was on Salo’s sledge with Mike. Salo needed no help at all when it came to running the dogs but plenty in muscling the sledge through drifts and to start it moving after breaks. Salo’s technique with the dogs was impressive. To his team he was the unchallenged “alpha-dog” and every member of the team symbolically genuflected before him. He tolerated no nonsense from them and could be absolutely brutal with any that stepped out of line. It was clear that every dog on the team loved and respected him.

The manner in which the dogs were run was (I’m searching for an adjective here)… interesting. Instead of using the central trace (gangline hitch) method common in most of the world, Greenlandic mushers invariably use the fan technique. In the central trace method the dogs are harnessed to a single tug-line in orderly pairs. In the fan method, each dog has its own tug-line and the individual lines are joined to the sledge by a single slip-knot. Advocates of the central trace method point to its inherent efficiency and the great maneuverability it gives sledges on narrow, heavily forested trails. Backers of the fan technique point out that it allows the dogs to find their own best path through rough ice and around other obstacles. They correctly note that there are no forested trails in Greenland.

…From the humble and non-expert perspective of all the members of our expedition who were not born in Greenland, we regarded the fan technique an invitation to disaster.

From the humble and non-expert perspective of all the members of our expedition who were not born in Greenland, we regarded the fan technique an invitation to disaster. Every morning we laboriously wrangled the dogs into position and clipped them into their tug-lines. We worked hard to prevent twists and tangles. No sooner than we turned our backs the dogs commenced leaping over each other to socialize, mate or do battle. It was the work of a moment for them to hopelessly tangle the lines. However, that was not the worst of it. The real problem was that once we got going they would continue to roam about and tangle each other to such an extent that one, two or half of them were lassoed so thoroughly that they could barely walk, let alone pull the sledge. Even Salo’s dogs were not immune to such shenanigans. For our dogs and the rotten team a day did not go by without the majority of them being hog-tied at one time or another.

All of this is not to suggest that we did not appreciate the dogs. They were our best and truest allies and performed astonishing feats of strength every day we were on the ice. The dogs were not particularly large (none of them weighed much more than 70 pounds / 32 kilograms) but each could pull double its weight all day long. In the intervals between the tangles, fights and their impromptu work stoppages they relieved us of a huge amount of drudgery.

Day #16 did not end for us until fifteen hours after our 3am wake up. Contrary to the prediction the weather remained nice all day long and Sigrid wisely determined to capitalize on it. We pushed hard, each of us doing two hour stints in the lead until we reached the long-anticipated GPS point for Summit. Although there were no neon signs welcoming us to the spot (and even more unusually, no Starbuck’s outlet!) we were infinitely gratified to be there. Our efforts yielded a best-to-date 24 miles (39 kilometers) of progress. Just as significantly, we passed the halfway point of our journey: 180 miles (290 kilometers) down and only 170 miles (274 kilometers) to go. We were at 8,138 feet (2,480 meters) above sea level. After struggling so hard to get to Summit we all looked forward to the descent to the coast. In my diary I rhapsodized about “the easy downhill slide to Isortoq.” As it turned out my optimism was naïve in the extreme.

Summit to Isortoq Turn (May 22-28)

Throughout our journey over the ice we kept our spirits high by focusing on attainable not-too-distant goals. It would have been overwhelming to fixate on something as unreachably remote as our coastal finishing line. After Summit our next goal was the GPS waypoint for Isortoq Turn. Isortoq Turn was the place where we would stop our eastward progress and turn south toward the coastal village of Isortoq. From our position at Summit, Isortoq Turn was a daunting 140 miles (225 kilometers) away.

Unfortunately, we awoke on the morning of May 22 (Day #17) to a furious blizzard. It was immediately apparent that travelling was out of the question. Sigrid went tent-hopping to fill everyone in on the latest weather report. The prediction was for the storm to blow itself out around midnight. Accordingly, our plan was to sit tight for the day and gather together for a group dinner at 5 pm. The best outcome we could hope for then was confirmation of a break in the storm. If it came we would leave the tents at 11 pm and sledge through the night to gain whatever miles we could.

With our crossing schedule (and flight arrangements for the trip home) in shambles, another problem arose to dominate our thoughts: we were running out of food. We had been provisioned for twenty-one days on the ice. The best outcome we could hope for now was to finish in twenty-four days. Although Sigrid indicated that there was an emergency cache of two days’ food 50 miles (80 kilometers) away, the uncertainty of finding it as well as its own frugality dictated that we had to begin rationing at once. Every one of us knew that the historical record shows that sledging and rationing do not make happy bedfellows. The food shortage was a frustrating development and a serious blunder on the part of the trip organizer.

…There was truly no rest for the weary on this expedition.

For me, being delayed by the storm was not all bad news. Our exceedingly long day yesterday had left me tired and it was a great pleasure to lay about in the cozy tent while the blizzard raged outside. Although I had lead-skied only two hours yesterday and split the rest of the time between mushing our team and assisting Salo on his sled, I found the sledging duties almost as taxing as lead-skiing. There was truly no rest for the weary on this expedition. Whether you started the day lead-skiing or on the sledges, you put your skis on in the morning the moment the packing was done and did not take them off until you stopped to make camp in the evening. In the interval you never sat down. Not once. The best you could hope for was to lean against the sledge during rest breaks. If you were lead-skiing, you just stood there during the hourly breaks. While the dogs often caught up with the lead skiers, Salo always stopped the dogs at least fifty yards short of them. There was never any communication between the lead skiers and mushers.

Everyone has seen videos of mushers racing across Alaska during the Iditarod. In that famous race the dogs pull at breakneck speed and the musher stands on a platform at the back of the sledge carried along by his team. Our mushing was not at all like that. First, there was no platform at the back of our sledges. The only appendage of any sort was an evil-looking saw-toothed brake between the runners that our skis bumped into with appalling frequency. Second, our dogs had their paws full with all our gear. It was unthinkable for them to carry us as well. Quite to the contrary, we needed to add our muscle power to help keep the train rumbling along. The best we could hope for was a free pull from the dogs when conditions were right. While mushing we all wore harnesses that we looped around the upright of the sledge to take advantage of whatever pull the dogs were willing to give. Sometimes we effortlessly “water skied” across the ice. Most of the time we trudged along pushing the sledge as we went. I found the work exhausting.

I was tenting with Chris and he was a great guy and congenial companion. He was unquestionably the hardest working member of our group, always the first out of the tents in the morning and assisting others with great generosity. While Sigrid was our head guide, Chris commanded universal respect and was like a second guide ready to step in at a moment’s notice. On top of everything else, he was the strongest skier and best navigator of the group. His Royal Navy training really came to the forefront when he was lead-skiing because his track was always impeccably straight and precisely directed. Not all the members of our expedition had this happy facility.

At our 5 pm dinner we satisfied ourselves with a light meal of ramen noodle soup. It reminded me of my days as an impoverished college student. But, the good news was that the weather gurus were still predicting abatement of the storm. Chris and I volunteered to be the first lead skiers and everyone agreed to start breaking camp at 11 pm. It was chilling just to think about that.

…It seemed like we were on an alien planet and the brutal cold put an exclamation mark on the strangeness of our fragile little party presuming to be there at all.

Our camp at Summit was about 10 miles (16 kilometers) below the Arctic Circle so we were no longer in the zone of twenty-four hour per day sunlight. When we got underway just before midnight it was bitterly cold and the light had a weird dusky character. There was plenty enough light to see where you were going but the reddish streaks and yellow banners in the sky combined with the deep blue of the ice gave an exotic quality to the surroundings that made the enterprise of skiing suddenly feel fresh and new. I tried to take mental snapshots of the scene as we went along. I have never in my life been so enthralled by a place while skiing. It seemed like we were on an alien planet and the brutal cold put an exclamation mark on the strangeness of our fragile little party presuming to be there at all. For the first time in days it occurred to me that I was in Greenland.

The journey through the night was highly successful. After Chris and I went back to the sledges, the pairs of Clare plus Anja and Mike plus Ian took their turns in the front. Throughout their leads the dogs were uncharacteristically cooperative. I took this as a harbinger of good days ahead and directly attributed it to the fact that we were now over the hump and going downhill. Sigrid wanted to take advantage of the dogs’ excellent behavior by taking a turn at lead-skiing herself. I joined her for a ninety minute stint up front. The skiing was very enjoyable because we had a strong wind at our backs. We would have kept going longer but for the fact that the increasing wind threatened to turn our camp building exercise into an epic. We quit skiing at 9am, 22 miles (35 kilometers) to the good.

More Night Skiing

During the day (May 23) we luxuriated in the tents while the wind screamed outside. I would have been happier with a bit more food inside me but felt great that our overnight run had yielded such a good result. Although it was cold throughout the day, inside the tent the temperature at 3pm rose to an astonishing 87°F (31°C). The greenhouse effect and two bodies in a small space were an incredible combination.

The whole team gathered together for another frugal dinner at 7 pm. We decided to do another night run because we thought that the day’s strong wind had hardened the snow and would make the going favorable for the dogs. We agreed to be out of the tents at 10:30 pm to start breaking camp.

As the hour for departure approached I was completely miserable. Eighteen days on the ice left me feeling worn out and the prospect of ten hours in the awful cold made my spirits plummet. It was minus 5°F (minus 21°C) and the wind was still blowing hard. Just putting on my boots was a terrible effort. Our camp was at over 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) and doing the simplest things took inordinate effort. I mentally cursed the madness that made me come to Greenland.

As comforting as it was to wallow in self-pity it was soon time to start skiing. Chris and I were first in the batting order and we got underway at ten minutes before midnight. As usual, Chris led and did the navigating. He set a blistering pace that left me no time for dolorous reflection. It was not long before I was happy once more. It was fascinating to see the frigid arctic dawn break at 2 am.

After an invigorating two and a half hour stint in the front we were relieved by Clare and Anja. When I went back to Salo’s sledge it was immediately clear that the dogs were having a difficult time. Instead of being hardened by the wind, the surface was carved up by sastrugi and had valleys of soft snow between. The dogs hated it. We had to push the sledges with all our strength to make any progress at all. Mike pushed so hard trying to get the rotten dogs’ sledge moving that he broke off one of the uprights. This was a true calamity because it made the sledge virtually unsteerable. Salo came back to work on a fix and the train ground to a lengthy halt. Meanwhile, Clare and Anja skied on and were lost from view by the thick mist which had enveloped the ice. Engaged in repairs, it was some time before anyone realized the two were lost in the void.

…When we noticed our teammates were missing, we immediately went in hot pursuit following their last known compass bearing.

When we noticed our teammates were missing, we immediately went in hot pursuit following their last known compass bearing. It was twenty tense minutes before we glimpsed them. Our relief was huge. On the immense icecap you never want to be out of sight. The consequences of being lost are dire and finding a lost party in the fog is uncertain at best. In this case, Clare was navigating and Anja was supposed to look back periodically to assure the dog sledges were still in view. Caught up in the effort of skiing, she failed to do so. Big mistake.

We plodded on through the wee hours and were glad to see the brutal cold abate a bit around 5am. We finally ceased our labors at 10am. A couple of hours before that my own worst nightmare came true when I saw that my right ski was separating from the binding. The failure point was the same one the left ski suffered two weeks earlier: a sheared center attachment screw on the Voile bindings. Instead of trying to fix it while on the trail we finished out the day as best we could. Chris cheered me up by saying he was confident that he could make the repairs.

When we went to earth in the tents at 11am on Day #19 (May 24) we were all feeling a bit strung out. Our two successive night runs, the difficulty of sleeping during the day and short rations combined to put everyone on edge. The upside was that we made a best-ever 25 miles (40 kilometers) of progress overnight and had edged to within 100 miles (161 kilometers) of Isortoq Turn. We figured that if we could continue to power through 25 mile days we would hit Isortoq Turn in four and finish out the trip in five. That was a very encouraging thought. At our group dinner we decided against doing another night run. Sentiment had swung back and forth on the issue and I was very happy when the final decision was “no.” I needed the rest and a wet snow would have made the going awful for dogs and men alike.

True to his promise, Chris fixed my ski. I was enormously relieved and set out with him on the morning of Day #20 with a grateful heart. Besides leading the train, our most important job was to find the small food depot Sigrid had left on her outbound journey to Dog Camp. If it were not for the uncanny accuracy of GPS and Chris’s sharp eyes we would have never found it. The small snow cairn that marked the depot was thoroughly eroded and only a short piece of green twine distinguished it from a thousand other bumps on the ice. It was a great relief to be able to add a few more meals to our larder. However, by the time our rotation up front was done it was apparent that the team was in for a tough day. The snow became softer and stickier as time wore on. Before long the runners of the sledges had sunk six inches (fifteen centimeters) into the snow and it took Herculean efforts to keep moving. The dogs did not like it one little bit. The only thing that saved us was that over the course of the day we dropped down 588 feet (179 meters). We ended the day 24 miles (38 kilometers) to the good.

I was so tired after my second rotation lead-skiing that I would never have been able to get Sigrid’s tent up without Ian’s help. I was tenting with her and it was always her tent-mate’s job to get the tent erected while she was putting the dogs down for the night. While I can solve a Rubik’s Cube with no trouble, the intricacies of her tent thoroughly eluded me. Ian noticed my addled state and selflessly jumped in to help. Great team members are a blessing in trips into the wild!

Plan for Early Relief

Progress over the next couple of days was intensely difficult and variable in results. A good day on May 26 netted us 25 miles (40 kilometers) but we struggled to get 18 miles (29 kilometers) on the next day. My rosy prediction of an “easy downhill slide to Isortoq” mocked me and my diary now spoke of Greenland as “this icebound hell on earth.” Miserable snow conditions persisted and our downhill progress, which we assumed would average over 1,200 vertical feet (366 meters) per day was nothing like that. I think every one of us was thoroughly sick of being on the ice.

Conscious of the fact that four of us had reservations to fly out of Kulusuk on May 30, a plan was evolved to get us off the ice in time to catch the flight to Reykjavik. Since Mike and Clare had flights several days later, they were content to let their arrangements stand. For the rest of us missing the flight meant days of delay because it only runs twice weekly. At first the plan was to have a helicopter pick us up at the water’s edge near Isortoq on May 29. However, this idea had to be abandoned when the weather report for the day turned sour. As it evolved, our only option was for a helicopter pick-up at Isortoq Turn on May 28. This was an iffy proposition for two reasons: 1) the weather was questionable and 2) Isortoq Turn was still a long way off.

…In Greenlandic the word “piteraq” means “that which attacks you.” I lived through a piteraq in 2014 and wanted no part of another one.

Following the disappointing 18 mile run on May 27 (Day #22) we were only able to catch a few hours rest before departing at 1 am for the anticipated 3 pm (May 28) rendezvous with the helicopter at Isortoq Turn. While we rested Sigrid passed along weather updates that were downright alarming. A blizzard was predicted for the night of May 28-29 and a full-blown piteraq was thought to be following on its heels. Piteraqs are katabatic storms of awesome destructive power. In Greenlandic the word “piteraq” means “that which attacks you.” I lived through a piteraq in 2014 and wanted no part of another one.

For us the calculus was simple. We would sledge through the night to cover the unheard of distance of 27 miles (44 kilometers). If the helicopter came, Ian, Chris, Anja and I would get an early escape from the ice. If it did not come we would take a few short hours rest and run for the sea overnight like our lives depended on it. I was dismayed by the thought of the excruciatingly long push to Isortoq Turn. I could not begin to contemplate what the trip to the water’s edge would be like.

When we left camp at 1 am in the morning of May 28 it was a tropical 19°F (minus 7°C). It was nice not to be cold but otherwise conditions were dreadful. It was actively snowing and four inches (ten centimeters) of unconsolidated powder blanketed the ground. The sledges bogged down and lead-skiing was greatly impeded by the effort of trail breaking. My memories of the day are fragmentary but after thirteen hours of effort we finally reached Isortoq Turn. Naturally, it was an undistinguished patch of ice no different from any other in the vicinity. When I checked my GPS I saw that I had been there before. It was virtually on top of one of the campsites I had occupied in 2014.

We quickly got Mike and Clare’s tent up and all of us gratefully collapsed inside. Sigrid unlimbered her satellite phone and called Air Greenland to see whether the helicopter flight was still on. I was on tenterhooks because the weather had settled into a decidedly ambiguous pattern. You could see the horizon and a “water sky” darkened the sky to our south. We knew that the ocean was less than 20 straight line miles (32 kilometers) away. However, gusty squalls created ground blizzards that I feared would doom our prospects for relief. I was elated when Air Greenland confirmed that the helicopter would leave Tasiilaq within an hour. The thoughts of a hot shower, comfortable bed and delicious meals were intoxicating. I was a bit disappointed that I would not get to see the village of Isortoq but not nearly so much as to consider continuing. During our long, long overnight trip I had been so fatigued that I had literally fallen asleep on my skis.

Mike and Clare, on the other hand, seemed genuinely happy with the prospect of continuing the trip all the way to Isortoq. They were curious to see an authentic Greenlandic village and, through signs and gestures, Mike had gotten Salo to agree to take him seal hunting. Supremely fit travelers that they were, Mike and Clare took the thought of another overnight sledging adventure in stride.

An hour later Air Greenland called and said the flight was off. If the tent had a window I might have leaped out of it.

We immediately went outside to erect the rest of the tents. It seemed a pity we would only be in them until midnight, just seven hours away.

Isortoq Turn to Isortoq (May 29)

I was tenting with Salo and we got organized quickly. Once inside we set to work melting ice and I snacked ravenously on every leftover bit of food that I had. When the water finally came to a boil I dug deep into the recesses of my bag to retrieve the single remaining freeze dried meal I knew was there. I triumphantly pulled it out only to discover that it was…curried cod flavor! Of course. I held the packet up for Salo to see and he immediately burst into gales of laughter. That was one of the best moments of the entire trip.

…when I emerged from the protection of the tent the wind struck me with such ferocity that I thought it impossible for us to proceed.

Against all odds, I was able to nap a bit in the run-up to midnight. However, when I emerged from the protection of the tent the wind struck me with such ferocity that I thought it impossible for us to proceed. The drift was flying horizontally and so thick that it was impossible to see more than fifty feet (fifteen meters) in any direction. I honestly thought Salo and Sigrid would take one look at conditions and order us back into our tents. Shouting over the storm I asked Sigrid whether we dared to proceed. Her answer was that with a piteraq coming we had no alternative but to go on.